Sophie White, associate professor in the Department of American Studies, has received a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH)—her second NEH award in five years—for her book project, Voices of the African Diaspora Within and Beyond the Atlantic World.

As one of two winners from Notre Dame’s College of Arts and Letters for 2015, White continues the University’s record success in earning NEH fellowships. Arts and Letters faculty members have been awarded a total of 53 NEH fellowships since 1999—more than any other university in the country.

“I was thrilled to receive the grant,” White said. “It is a validation of the work I’m doing and also motivation to complete the project.

“I am very grateful to Notre Dame for all the support it has provided me over the years, especially through the Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts. Without those grants, I would not be in the position to be awarded an NEH fellowship now, because ISLA helped fund my earlier research.”

A Rare Public Forum

White, who is a concurrent associate professor in the Department of Africana Studies, the Department of History, and the Program in Gender Studies, is analyzing courtroom testimony from enslaved Africans in French colonies, primarily in 18th-century Louisiana.

Individual slaves did not often have an avenue to tell their life stories, White said, as French colonies had no tradition of documenting their biographical accounts. But when called to testify in court—either as defendants, witnesses, or victims—the enslaved had a rare public forum.

“In French law, testimony and confession are key,” she said. “In these trial records, there is extensive questioning, and I’m arguing that there is a lot of room for slaves to intersperse other information and to give us a sense of who they are or who they would like to project they are to the court.”

Many slaves seized the opportunity and sought to voice their experiences of slavery and removal from their homelands. Court clerks often acknowledged these moments in their transcriptions, White said, as they commented that a slave witness “said, again without being asked,” or that a slave defendant “said on her own initiative.”

“It is no longer about the court case,” she said. “It becomes about other things they want to share, which is what makes this interesting. This testimony is forced; they have no choice but to appear. But, in spite of that constraint, there is still the potential for an autobiographical narrative.”

A Rich Repository

The trial records from Louisiana prior to France’s 1769 cession of the colony provide a rich repository, White said. The transcripts contain testimony from nearly 150 distinct voices of Africans and African descendants.

One example she found particularly compelling involved a group of enslaved women doing laundry by the Mississippi River in New Orleans in 1752. A drunken French soldier attacked them and was later charged with the crime.

When one woman was called to testify in court, she recounted how the man had threatened her with a bayonet and ordered her to “kneel and ask his forgiveness.” According to her court testimony, she replied that “one only asks God for forgiveness.”

“I’m intrigued by that, because it tells me quite a lot about how she’s presenting herself,” White said. “She’s positioning herself as someone who could speak back to a Frenchman. She could get in big trouble for that, but she’s saying she did it because she is claiming the moral and religious authority over him.

“You get a very strong sense here of playing with religion. She was owned by the Ursuline nuns, and her words signal that Catholicism and knowledge of prayer and confession mediated her interpretation.”

Notre Dame has proven an ideal place for her research, White said, as it has heightened her awareness of religious elements infusing slaves’ accounts in French (and Catholic) colonies.

“Many people have seen that testimony, but I don’t think anyone has gotten as excited as I have about a slave belonging to women religious speaking back to a young Frenchman,” she said. “I am attuned to that because of where I work.”

An Emotional Exchange

White specializes in early American history with an interdisciplinary focus on cultural encounters between Europeans, Africans, and Native Americans, as well as a commitment to Atlantic and global research perspectives.

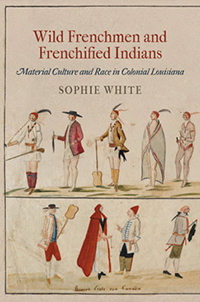

Her first book, Wild Frenchmen and Frenchified Indians: Material Culture and Race in Colonial Louisiana, examines perceptions of natives in French colonial Louisiana and demonstrates that material culture—especially dress—was central to the elaboration of discourses about race.

Looking ahead, White hopes to undertake a comparative project exploring autobiographical narratives in judicial testimony from French colonies around the world. She has begun conducting archival research in her native country of Mauritius—an island nation near Madagascar—which has also helped her contextualize her current project within a global French empire.

While in Mauritius recently, she attended a UNESCO-sponsored conference commemorating the abolition of slavery. There, she heard powerful stories from descendants of slaves, who in turn were fascinated by the accounts from her research that she shared.

For White, these emotional exchanges brought new meaning to her work.

“I’ve never before experienced a hunger from a local population to know what I’m doing; usually, it is other academics,” she said. “But it’s important to them to know that the enslaved did find ways to speak up.”

A Compelling Narrative

White, who last fall taught a course on captives and slaves in the New World, said it’s also important for her students to hear these stories about life without freedom.

“There is a lot of violence and negativity in the trials, but what these witnesses want to talk about is often something very different,” she said. “There is joy in there, as well. There are tales of going to see loved ones, tales of relationships and community that come through.

“When we have this kind of evidence—when we can hear these words—we owe it to these individuals to pay attention.”

Originally published by at al.nd.edu on April 29, 2015.