Citation for the 2017 Laetare Medalist, delivered by Mr. John J. Brennan, chairman, Notre Dame Board of Trustees

Father,

To recognize and praise you, as we justly do today, for your 30 years and more of service in the gang-riven barrios of East Los Angeles is no more than to acknowledge a civil deed well done:

Homeboy Industries, that quixotic bakery-café-silkscreen-embroidery-landscaping “homie-staffed” enterprise you founded in 1988, has now become the largest gang intervention, rehabilitation and re-entry program in the world. Ten thousand souls a year avail themselves of its therapeutic and educational offerings, the practical services it offers such as tattoo removal and job training, and the escape route it provides for men and women trapped in cycles of violence and incarceration and longing to transform their lives so as to rejoin and support a more hopeful and humane society.

This, of course, is much, but you have done more.

You have exemplified the ancient imperative at the wellspring of a faith ever new: “Where there is no love, put love, and you will draw forth love.” That counsel, given by Saint John of the Cross to a troubled correspondent in the 16th century, is counsel you yourself give and stand by in the 21st.

As a fledgling Jesuit, you learned from Ignatius “to see Jesus standing in a lowly place,” and to that lowly place, that scourged, graffiti-scarred, inner-city conflict zone in and around Dolores Mission Church, you went to meet Him, to embrace and be embraced by your outcast, wounded and garishly tattooed Lord. You soon learned how much more He desired of you, and of us, than mere social work:

“We are not invited to rescue, fix or save people,” you once said. “The heart of ministry is to receive people and then enter into the exquisite mutuality God intends for us all. This is the essence of a ministry that empowers by listening, receiving and welcoming. My life is saved every day by contact with folks who are at the margins. And the day won’t ever come when I am more noble, have more courage or am closer to God than these people.”

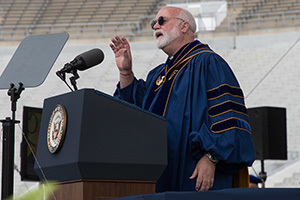

The University of Notre Dame bestows its highest honor, the Laetare Medal, on

Reverend Gregory Joseph Boyle, S.J.

Los Angeles, California

Rev. Gregory J. Boyle, S.J., receives Laetare Medal

Rev. Gregory J. Boyle, S.J.

Rev. Gregory J. Boyle, S.J.

Original release from March 26, 2017.

Wow. I had no idea I was bald. Thank you, Notre Dame, for pointing that out.

Father Jenkins and Class of 2017, I’m grateful for your kindness. The homies in 30 years have taught me so much in humility and fidelity. There’s a homie named Joey who we went out to dinner; Joey is about 30 years old and kind of our called-upon speaker to go to high schools, and he’s pretty good at it, much in demand, and he was giving me tips on how to speak publicly. He said, “You know, you gotta pepper your talk with self-defecating humor.”

I said, “Yeah, no shit.” That’s some good advice there. Embrace yourselves.

You know, what Martin Luther King says about church could well be said about your time here at Notre Dame: “It’s not the place you’ve come to, it’s the place you go from,” and you go from here to create a community of kinship such that God, in fact, might recognize it. You imagine with God a circle of compassion and then you imagine nobody standing outside that circle. You go from here to dismantle the barriers that exclude.

And there’s only one way to do that: and that is to go where the joy is, which is at the margins, for if you stand at the margins, that’s the only way they’ll get erased, and you stand with the poor, and the powerless and the voiceless. You stand with those whose dignity has been denied, and you stand with those whose burdens are more than they can bear, and you will go from here and have this exquisite privilege once in a while to be able to stand with the easily despised and the readily left out, with the demonized so that the demonizing will stop, and with the disposable, so the day will come when we stop throwing people away.

You go to the margins, and indeed you have to brace yourselves because people will accuse you of wasting your time. But the prophet Jeremiah writes, “In this place of which you say it is a waste, there will be heard again the voice of mirth and the voice of gladness, the voices of those who sing.” You go from this place so that other voices get to be heard, and you go equipped with values so eloquently articulated by C.J. earlier, values born in the Acts of the Apostles: see how they love one another. There’s nobody needy in this community.

And my favorite one is an odd one, and it says simply, “And awe came upon everyone.” It would seem that the health of the communities that you go from here to create may well reside in their ability to stand in awe at what the poor have to carry rather than stand in judgment at how they carry it.

I’m going to tell one story because I’m the only thing standing between you and lunch. Many years ago, I was invited to speak to 600 social workers in Richmond, Virginia. It was an all-day gang inservice from 9:00 to 5:00. I said yes, I figured I’ll give the keynote or maybe I’ll speak at lunch or maybe I’ll close the day. Well, a week before I was to fly, I pull out the letter, and to my horror, I discovered that I was to be the only speaker all damn day.

So I quickly called in two homies, José and Andre, gang members who were in our training program, and I sat them down, and I said, “Look, you’re flying with me to Richmond, Virginia, at the end of the week. I’d like you to get up and tell your stories. Take your time because we’ve got a long-ass day to fill.”

Well, I had never heard their stories, and José got up, and he was 25 years old, a gang member, been to prison, felon, tattooed, he was in our 18-month program, but he was finishing up his time as a very valued member of our substance abuse team – a man solid in his own recovery, and now he was helping younger homies with their addiction issues. He had spent a long stretch of time as a homeless man and an even longer stretch as a heroin addict. A gentle, kind soul. He’s proof that only the soul that ventilates the world with tenderness has any chance of changing the world.

So José got up, and he said, “I guess you could say I was six years old, and my mom and I, we didn’t get along so good. She said to me once, ‘I wish you would just kill yourself. You’re such a burden to me.’”

Well, 600 social workers audibly gasped, and he says, “It sounds way worser in Spanish,” and we went from gasp to laugh.

He said, “I think I was nine when my mom drove me down to the deepest part of Baja, California, and she walks me up to an orphanage and she knocks on the door, and the guy comes to the door, and she says, ‘I found this kid’’ and she left me there for 90 days until my grandmother could get me out of where she had dumped me, and my grandmother came and rescued me.

“My mom beat me every single day of my elementary school years with things you could imagine and a lot of things you couldn’t. Every day my back was bloodied and scarred. In fact, I had to wear three t-shirts to school each day: first t-shirt because the blood would seep through; second t-shirt you could still see it; finally the third t-shirt you couldn’t see any blood. Kids at school, they’d make fun of me, ‘Hey, fool, it’s 100 degrees, why you wearing three t-shirts?’”

And then he stopped speaking, so overwhelmed with emotion, and he seemed to be staring at a piece of his story that only he could see. When he could regain his speech, he said through his tears, “I wore three t-shirts well into my adult years because I was ashamed of my wounds. I didn’t want anybody to see them. But now I welcome my wounds. I run my fingers over my scars. My wounds are my friends. After all, how can I help heal the wounded if I don’t welcome my own wounds?”

And awe came upon everyone.

The measure of our compassion lies not in our service of those on the margins but only in our willingness to see ourselves in kinship with them.

Notre Dame is not the place you’ve come to. It always was going to be the place you go from, and you go from here to create a community of kinship such that God might recognize it.

My sense of the Class of 2017 is that you have ceased to care whether anyone will accuse you of wasting your time. For in this place of which you say it is a waste, there will be heard again the voice of mirth and the voice of gladness, the voices of those who sing.

For you have decided to go from here and to allow other voices to be heard, and may God bless you in that, Class of 2017.

Thank you.

Originally published by at news.nd.edu on May 21, 2017.