The Russian Revolution of 1917 is a defining event of the twentieth century.

In recent years, historians have come to see the revolution as a deep process beginning in 1905 and the First World War and extending into the early Soviet period as the laboratory for transformation. In some ways attention has shifted focus away from the year 1917 itself, as scholars have looked at processes across the accepted temporal divides of war and revolution. They have moved away from the first wave of revisionist studies that embraced society (primarily industrial workers), the army and especially the political parties, and turned to forgotten social groups (peasants, entrepreneurs, and white collar workers), the nationalities, and questions of identity and the borderlands, cultural history, new political history, the question of gender and so on.

The time is right to bring these new topics and visions together to provide a fresh overview of 1917 itself, but also an overview that will include the crucial earlier phases of the revolutionary process.

This new focus on 1917 will consider such questions as the politics of the February Days and from March through October, the practice of power (Provisional Government, Soviets, public committees, people’s courts, other infrastructure), the cultural front, empire and revolution, foreign policy, Russian military in the war, theories and practice of justice, regulation of the economy, reassessment of gender roles. There is much exciting new scholarship to be highlighted here.

Sponsored by the Nanovic Institute, this conference and subsequent volume will bring together world’s leading scholars of the Russian Revolution from the United States, Russia, England, Ireland, Germany, Israel, and Scandinavia to assess and often challenge the last hundred years of scholarship and to integrate the latest research based on much freer access to the previously closed Soviet archives.There is also the question of influence. The Russian Revolution called forth counter ideological and political movements from the right and challenged the liberal democratic republican consensus inherited from the French Revolution. The Russian Revolution was the model for national liberation and socialist movements globally. Finally, the Russian Revolution is intrinsically interesting as a laboratory of complex and violent historical transformation. It also reveals the great power of ideology (and politics) in history.

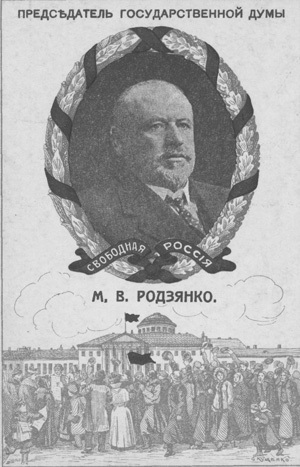

Russian Revolution of 1917, Wikimedia Commons

Contributions reflect the impact on the study of the Russian Revolution made by the collapse of the Soviet Union and the rise of new authoritarian regime of President Putin. At the same time, the conference will exemplify and promote new opportunities for collaboration between Western and Russian historians as we approach the centennial anniversary of Russia’s failed democratic revolution.

Russia’s Failed Democratic Revolution,

February-October, 1917: A Centennial Reappraisal

A Symposium on March 10-12, 2016

University of Notre Dame Rome Global Gateway

Opening Remarks by Semion Lyandres

Historiographies of 1917

Chair: Michael Hickey

- Lutz Häfner, ‟Aurora, or the ‛Last Days of Mankind’? The German Historiography on the Russian February Revolution after 1990 and Its Future Perspectives”

- Vera Kaplan, ‟Israeli Historiography of the 1917 Revolution(s)”

- Hannu Immonen, ‟From February Revolution to Civil War: Finnish Historians and the Year 1917”

Historiographies of 1917, Part II

Chair: Daniel Orlovsky

- Rex A. Wade, on the revolution at one hundred, and on issues and trends in the English language historiography

- Semion Lyandres and Andrei Nikolaev, ‟Февральская революция и Государственная дума в исследованиях российских историков последних лет”

- Taras Karaulshchikov, ‟Mikhail Aleksandrovich Polievktov and His Concept of the Fate of Russian Autocracy: Writing About the Reign of Nicolas I During the Great War and the 1917 Revolution”

Revolutionary Petrograd

Chair: Adele Lindenmeyer

- Toshi Hasegawa, ‟Crime, Police, and Samosudy in Petrograd in the Russian Revolution: the Subalterns, and Sociological Theories of Anomie and Crowd Psychology”

Revolutionary Personalities

Chair: Tsuyoshi Hasegawa

- Adele Lindenmeyr, ‟‘The First Woman of Russia’: Countess Sofia Panina and Women’s Political Participation in the Revolutions of 1917”

- Sarah Badcock, ‟Personal and Political Networks in 1917: Vladimir Zenzinov and the Socialist Revolutionary Party”

- Ekaterina Gavroeva, ‟М.В. Родзянко и князь Г.Е. Львов (весна – лето 1917г)”

Workings of Revolutionary Power

Chair: Sarah Badcock

- Michael Hickey, ‟Lost in the Vermicelli? The Provisional Government and Local Administration in Smolensk Province”

- Alistair Dickins, ‟Rethinking the Power of Soviets: Krasnolarsk, Michar-October 1917”

- Ian Thatcher, ‟Russian Political Parties and the First Provisional Government”

- Daniel Orlovsky, ‟The Question of Power in Late Summer and Autumn 1917”

Concluding Remarks by Semion Lyandres

This conference is supported with additional contributions from the Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts, College of Arts and Letters, Henkels Lecture Series and The Helen Kellogg Institute for International Studies at Notre Dame.

Originally published by at nanovic.nd.edu on March 03, 2016.