Nina Glibetić

Nina Glibetić

Being in the right place at the right time can change everything.

For Nina Glibetić, witnessing a chance discovery changed her research focus — and the trajectory of her career.

Glibetić, an assistant professor in the Department of Theology and a faculty fellow at the Medieval Institute, was on Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula in 2011, conducting research for her dissertation on Slavonic manuscripts when the head librarian of St. Catherine’s Monastery walked into the room to photograph some Ethiopic texts for another scholar.

As he took photos, the librarian discovered that one folio of parchment had a script that didn’t look quite like the others, and he showed it to Glibetić.

“I recognized immediately that it was Glagolitic, the oldest Slavonic alphabet,” she said. “I just happened to be there — it was a complete accident or providence — and he said, ‘Great, I can’t read it. Take this and work on it.’”

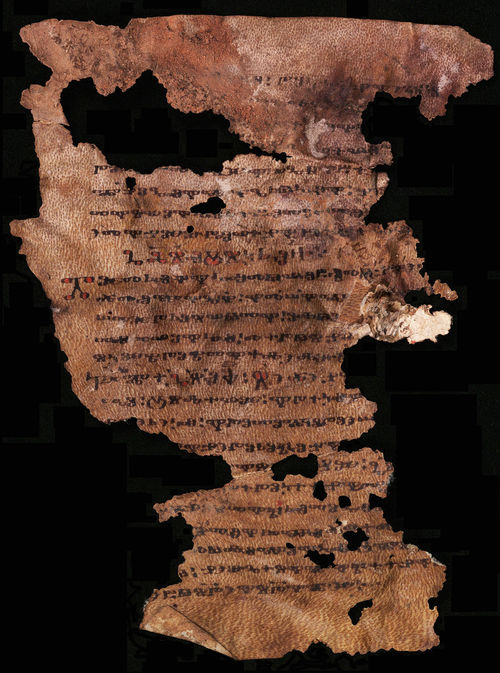

Early Glagolitic texts are extremely rare — only about 20 are left in existence. And that 11th-century folio turned out to be one of the oldest, if not the oldest, Glagolitic texts of the Serbian people, and one of the oldest Slavonic texts in any context.

An 11th-century folio that is one of, if not the, oldest Glagolitic texts, which Glibetić is translating and interpreting.

An 11th-century folio that is one of, if not the, oldest Glagolitic texts, which Glibetić is translating and interpreting.

Beyond that, the fragment is also helping Glibetić and other scholars make sense of the history of the multicultural monastic movement at St. Catherine’s.

“This was a very significant find because it opened up a whole conversation about why there are Glagolitic manuscripts there,” she said. “We’re now having to rewrite what we know of the Slavic presence in the Holy Land. And the bigger question is, what is the identity of this monastic center that had all these Christian communities living there simultaneously?”

An exciting discovery

St. Catherine’s Monastery is one of the oldest Christian monasteries in the world that is still in use. It is unique not only in terms of Christian history in the Holy Land, Glibetić said, but also in the preservation of texts and ancient languages.

From the fourth century on, it has attracted Christians from all over the world, and because of its desert location and dry climate, the materials stored there — including some of the oldest known fragments of the Bible and ancient books in numerous ancient and medieval languages — have been well preserved.

“Next to the Vatican, it’s the most exciting collection of manuscripts from the Christian world,” Glibetić said. “And it creates an interesting picture about Christian identity in the first millennium as far less fragmented than we tend to think of it.”

The folio Glibetić encountered belongs to a liturgical book of the hours, created at a time when the daily cycle of prayer was not stable — it varied from place to place.

“What’s exciting is that when a book has strong local features, it can be used to identify where the book was created,” Glibetić said. “This seems to be a midnight prayer by monks as it was done at St. Catherine’s — so this may be the first proof that Glagolitic books were copied there, and not necessarily brought there.”

The folio’s condition presented challenges — partially cut off and smeared with mud and insect marks, it took Glibetić over a year to decipher, using various photo technologies to help enhance the text.

Glibetić had also never worked with Glagolitic before 2011. But the discovery immediately inspired her to begin focusing on early Slavonic literacy as well.

“Glagolitic is an alphabet I studied for about two weeks when I did an introduction to Slavonic languages,” she said. “So when I found this fragment, I could slowly read some of it, but I was trying to quickly relearn Glagolitic late at night while staying at the monastery so that I could work with it properly.”

“What’s exciting is that when a book has strong local features, it can be used to identify where the book was created. This seems to be a midnight prayer by monks as it was done at St. Catherine’s — so this may be the first proof that Glagolitic books were copied there, and not necessarily brought there.”

An ideal home

Glibetić, who focused on Byzantine liturgy while earning her Ph.D. in eastern Christian studies at the Pontifical Oriental Institute in Rome, joined the Department of Theology in 2018.

Her background in liturgical studies not only drew her to Notre Dame — which has one of the oldest and largest programs in the U.S. — but is also an asset in her role as a member of an international research team dedicated to studying the Glagolitic manuscripts at St. Catherine’s, based at the University of Vienna.

Glibetić with head librarian at St. Catherine’s Monastery on Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula.

Glibetić with head librarian at St. Catherine’s Monastery on Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula.

“It’s been really interesting working with them because they often bring highly specialized philological and digital humanities skills, but most do not have any training in liturgical studies,” she said. “Often, what they’re missing is that historical-liturgical narrative — and that’s my area of expertise.”

Glibetić has published an article on this most recent folio and now, together with the same team, she is working on a collaborative book project on another early Glagolitic text known as the “Sinai Missal,” an 11th-century book that shows how some medieval Slavic Christians combined diverse Byzantine and Roman liturgical customs, despite the growing estrangement between east and west at the time.

On Nov. 16, she will also share her findings in a lecture and Q&A on campus, titled “Treasures of the Sinai Desert: The History and Marvels of the Ancient Monastery of St. Catherine” as part of the College of Arts and Letters Saturday Scholar Series.

Notre Dame, she said, is an ideal home for her research in a multidisciplinary field like liturgical studies.

“The University has one of the top medieval studies programs in the country and is developing a very good Byzantine studies program,” she said. “It also has a long legacy of original research in liturgical history, considering Christian worship as it developed over time and across space and situating it within both its theological and cultural context.

“Archaeology, visual evidence, manuscript studies, theology, musicology — all these things converge in studying the ritual act of the church, which is worship. The ideal circumstance is to have experts in all of these areas in a scholarly community, and when you do, it’s amazing.”

St. Catherine’s Monastery is one of the oldest Christian monasteries in the world that is still in use.

St. Catherine’s Monastery is one of the oldest Christian monasteries in the world that is still in use.

Originally published by at al.nd.edu on October 09, 2019.