Though the class Ana Lidia Flores-Mireles teaches this semester at the University of Notre Dame focuses on the clinical manifestations and current challenges of infectious diseases, she could not have planned its synchrony with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Flores-Mireles, the Hawk Assistant Professor in the Department of Biological Sciences, was set to talk about past pandemics. She had projects planned that showed students how treatments were invented. A professor who likes students to complete hands-on work, Flores-Mireles recently demonstrated the effectiveness of hand sanitizer by having them touch a surface with their thumbs, and then make an imprint on a petri dish. The dish was filled with bacteria. When students repeated the procedure after using hand sanitizer–it was clean.

“Think about how relevant this is now,” she said, referring to the COVID-19 pandemic that has swept the globe and moved her classroom online.

She and others within the department have adopted ways of teaching that can remain effective and as interactive as possible, depending on the course.

“While nothing can replace the excitement of student-filled classrooms and laboratories, our faculty have risen to the current challenge and are doing their best to ensure that our students receive a quality online education through the use of a variety of interactive platforms,” said Crislyn D’Souza-Schorey, chair of the Department of Biological Sciences. “The innovation, creativity, dedication and commitment demonstrated by so many of my colleagues have been inspiring, and because of this, we continue to forward our mission of providing an unsurpassed undergraduate education, despite the difficulties of the present time.”

Kristin Lewis, associate teaching professor in the department, said the introductory biology course already had a high degree of structure including weekly outlines on Sakai—the already-online learning and educational content management system—daily pre-class reading and preparation, and post-class assignments online. This was a benefit when moving to an online platform.

“The main challenge was to move our in-class content and activities to a combination of pre-recorded video and live Zoom help sessions,” Lewis said. “We feel confident that the structure of the course will continue to support mastery of biological concepts, and help students keep pace with their learning in what is a new fully online environment for the course.”

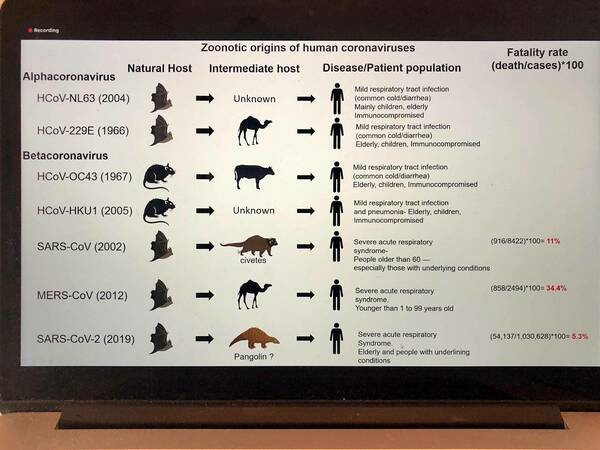

In Flores-Mireles’ class, student input drove some of the changes she made to her plans. When one student asked her to focus some lectures on the latest pandemic, Flores-Mireles created slides showing the structures and evolution of the virus, as well as how the virus likely changed so as it moved from bats to pangolins to humans (most recent studies indicate the disease likely progressed in this way).

There is also a “game” on the CDC website that instructors and students can use to investigate an outbreak, and she plays audio clips for students of the movie “Contagion” because it provides an engaging learning tool that relates to current events..

Felipe Santiago-Tirado, assistant professor of biology, felt his first lecture during an online session was not interactive enough, and he wanted to ensure his message was getting through to students. To make the class more engaging, he began using the Poll Everywhere app, which allows students to use their phones to answer polls based on the readings he assigned before class began, as well as past and current lecture content.

Now he is able to see how many have answered a multiple-choice question correctly, and then knows if he needs to revisit a topic or describe it more thoroughly.

“In a regular class, I can easily ask them and see their faces, but this app is a very good way to see their understanding,” he said, adding that it has been so useful that he will consider using it when classes return to their in-person format.

Maura Lee, a junior majoring in science-business, likes the method Santiago-Tirado is using, and so does Madelyn LaBar, a senior majoring in biological sciences.

“It breaks up the lectures a bit,” Lee said. “I really appreciate how hard he is trying to make his lectures more engaging, since we are not physically there to learn.”

Santiago-Tirado also uses the chat feature on Zoom, LaBar said, which helps keep her interested in class. “I also think it is important that Professor Santiago-Tirado is using Zoom instead of other methods such as recording lectures or posting on forums, as I am doing in other classes, because it is much easier to engage in the course this way,” she said.

Michelle Whaley, teaching professor, teaches one of the five laboratory courses that serve some of the 530 students who take introductory biology. Her course is

paired with the research laboratory of Professor Joseph O’Tousa, and she is able to use methods and data from his lab to give to students.

“What we do is data analysis, watch videos on technique, and how to do each step; I feel good about what they’re learning,” she said. “They’re getting good technical information on lab experiments, along with data to complete an original project.”

Though lab instructors are not able to meet with students individually as often as often as they were, Whaley said, she and others offer review sessions and office hours, which will become more important as the students begin writing their research papers. “I feel pretty pleased with the way things are going,” she said.

Lewis said that many professors are using Gradescope, an online grading platform to manage assignments, quizzes and tests. Students have a relatively wide time frame in which to complete quizzes, but there is a time limit once they begin.

“Many of our questions require students to apply information so they aren’t able to simply look up something in their notes,” she said. “They would need to understand the concepts well.”

Flores-Mireles has a final project planned for her course. Students are required to propose a new therapy for a disease she has assigned them. They need to “solve” the epidemic after several steps, including developing a phylogenetic tree to show how closely related one disease is associated to another illness.

“And if they have a therapy, they have to determine why that therapy will not work for another disease even if it’s closely related,” she said.

It’s not unlike what researchers around the world are doing for COVID-19.

Originally published by at science.nd.edu on April 08, 2020.