Roy Scranton was writing.

He was in Oklahoma, in his last year of Army service and just back from a tour in Iraq. He was crafting a fictional character named Wilson, an American poet and Army private in the middle of a tour in Iraq.

But he knew that couldn’t be it. There had to be more. The story of the Iraq he had seen needed multiple perspectives.

“That seemed essential to me from the very beginning,” he said. “I knew Hemingway and Tim O’Brien and a bunch of other war literature in the American tradition, and I knew that wasn’t good enough. To just talk about, ‘I went to war and war is hell and now I’m telling my story’? I needed to write about the people who lived there — and also how that connects to here. All those people had to fit together somehow.”

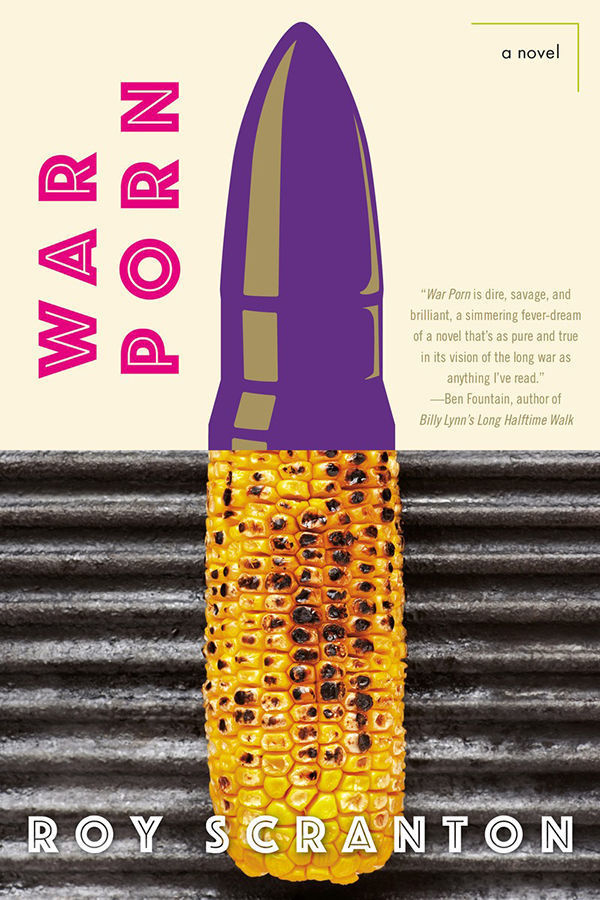

That complete portrait of Iraq is on display in War Porn (Soho Press, 2016), the debut novel by Scranton, who joined the Notre Dame Department of English as an assistant professor in fall 2016.

Wilson is still in it, but the narrative also includes a group of friends at a Utah barbeque and an Iraqi mathematician named Qasim, whose life is profoundly shaped by the American invasion of the country he calls home.

The result, chief New York Times book critic Michiko Kakutani wrote in her review, is a “forceful and unsettling” portrait of war from a writer with “myriad gifts as a storyteller.”

“In War Porn, Scranton has found a way for America to move beyond the hero cult we’ve built around our military,” the New Republic says in its review. “Without any moralizing, he offers an undeniably courageous book that depicts war as a corrosive force that corrupts everyone it touches. The book offers a guided meditation on Iraq certain to force long overdue introspection on how we think about the war, those who fought it, and the Americans and Iraqis it affected.”

Roy Scranton was writing.

He was in Moab, Utah, in the late 1990s, mingling with a community of poets and memoirists, including Terry Tempest Williams. He wound up there after dropping out of college and toiling through a menagerie of odd jobs — dishwasher, breakfast cook, phone psychic, hot dog stand operator. He worked full-time for a while as a grassroots organizer for the Fund for the Public Interest in Oregon, but quit as he began to have less and less time to write.

So he went to the Utah desert, writing and working more odd jobs, thinking that might be his life. Then three things happened in close sequence.

A key writing mentor died. Scranton was in a terrible bicycle accident and had no health insurance. Terrorists hijacked four planes on 9/11.

Roy Scranton, in Iraq in 2003.

Roy Scranton, in Iraq in 2003.

That series of events forced him to think about mortality, his future, and how the world was changing. Growing up in a military family, enlisting had always seemed like a possibility — but now, the Army was his path to a paycheck, health care, and college.

It was also his path to experiencing a critical point in history.

“I wanted to see it and understand it,” he said. “If I’d grown up in a middle- or upper-class family and gone to a great school, I probably would have tried to go there as a journalist, but that wasn’t available to me. This was the way I could see what American empire looked like. It was a chance to look at this existential conflict between terrorism and our way of life. I wanted to go see what it meant and what it cost and see if I could say anything about it.”

He served in the Army from 2002 to 2006, spending 14 months deployed in Iraq. At first, he thought he could be objective about his experiences — do what he needed to do, analyze what he saw, then write about it. He quickly realized that would not be true at all.

“This experience was shaping and changing me. There was no way I could sit back and observe. You’re always in it,” Scranton said. “It seems obvious, intellectually, but it was something I struggled to understand — how that experience is changing you in ways you don’t even know yet.”

Roy Scranton was writing.

He was at Princeton University in 2015, close to finishing his Ph.D. in English, and set to publish two important works.

The first, an essay in the LA Review of Books, sparked controversy by detailing a concept Scranton calls “the trauma hero.” American politics, news, and pop culture, he argues, is flush with stories of naive American boys who go to war, discover truth on the battlefield, then return home as tattered and scarred men.

That narrative distances the American public from the true consequences of war, he contends, especially atrocities committed by U.S. troops.

“Since World War II, it seems like the American story of war has focused more and more on how hard it is for Americans, how bad Americans feel when they have to go kill other people,” Scranton said. “And then the other people get left out, or they show up as a way for the Americans to talk about how bad the Americans feel. And that just doesn’t feel right.”

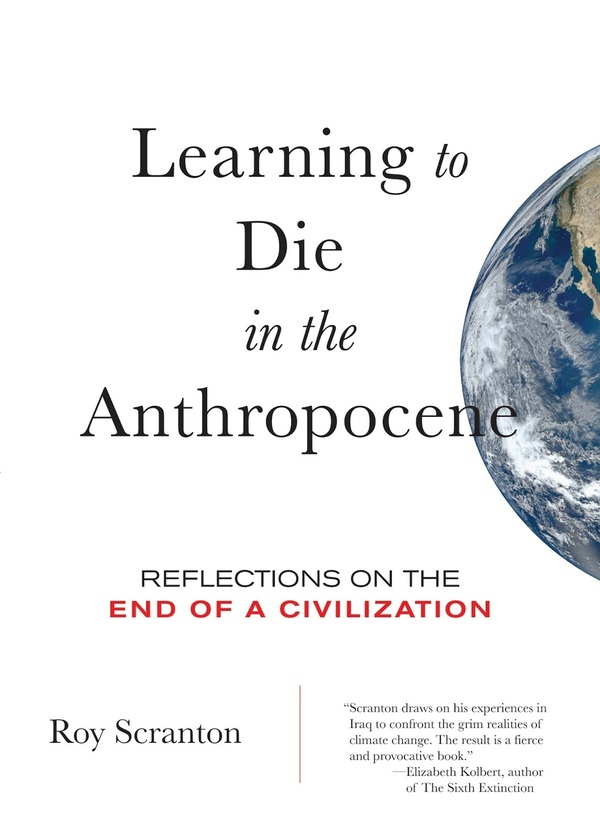

Later that year, Scranton released Learning to Die in the Anthropocene, a reflection and treatise on the implications of global warming and the need for serious contemplation about the end of the Earth as humans have known it.

“The biggest problem we face is a philosophical one: understanding that this civilization is already dead,” Scranton wrote in a similarly titled piece for The New York Times. “The sooner we confront this problem, and the sooner we realize there’s nothing we can do to save ourselves, the sooner we can get down to the hard work of adapting, with mortal humility, to our new reality.”

Scranton, on the Tigris River in Baghdad for a Rolling Stone article in 2014.

Scranton, on the Tigris River in Baghdad for a Rolling Stone article in 2014.

How did he get from Iraq to the Ivy League? After his service ended, Scranton used his GI Bill funding to earn bachelor’s and master’s degrees in liberal studies at The New School in New York City. He considered pursuing an MFA or a doctorate in either philosophy or English, ultimately choosing to study the latter at Princeton.

Along the way, he co-edited a collection of short stories about Iraq and Afghanistan and wrote criticism, scholarship, and poetry. His journalism has appeared in Rolling Stone, which sent him back to Iraq a decade after he left the war, and in The New York Times, including an opinion piece on a confounding trick Star Wars has played on American audiences.

“Looking out over Baghdad on the Fourth of July,” Scranton wrote, “I saw the truth that story obscured and inverted: I was the faceless stormtrooper, and the scrappy rebels were the Iraqis.”

Roy Scranton is writing.

He’s currently working on a scholarly book, The Politics of Trauma: World War II and American Literature, that draws from and expands on his dissertation. Scranton aims to detail how a wide variety of texts replaced the heroes of industrial capitalism with narratives of war trauma.

Why America remains so connected to old-fashioned stories of heroic sacrifice is complicated, Scranton said, but likely grows out of the controversial nature of recent U.S. wars. Trauma myths, he contends, prevent deaths in those conflicts from becoming politically messy, while also diverting attention from the deeds of soldiers.

“It evacuates the agency of the actors,” he said. “The story is ‘War gets inflicted on this guy and he suffers for it and he suffers from it.’ The trauma hero is the victim in that situation, and that erases the actual victims of violence.”

At Notre Dame, Scranton is teaching fiction and nonfiction writing. He’s been impressed by how engaged and talented his undergraduate students are and is invigorated by the faculty in the Department of English and the Creative Writing Program.

“I’m excited by the kinds of things — the weird, experimental, interesting stuff — that my colleagues in creative writing are doing,” he said. “And I’m especially excited about the creative and scholarly ambition at Notre Dame, the desire to really go toe-to-toe with the country’s top institutions in an intellectual way.”

I’m excited by the kinds of things — the weird, experimental, interesting stuff — that my colleagues in creative writing are doing. And I’m especially excited about the creative and scholarly ambition at Notre Dame.”

Originally published at al.nd.edu.