On April 17, 1675, an elderly Frenchwoman died from breast cancer in her grand home in Paris. Her name was Marie de Vignerot, but she was known best by her title, la duchesse d’Aiguillon. Several days later, a priest named Jacques-Charles de Brisacier eulogized her at the church of the Séminaire des Missions Étrangères de Paris, a seminary she had helped to found. In front of many clergymen gathered there that day, Brisacier lauded the powerful Duchesse d’Aiguillon as more like a bishop than like a typical aristocratic lady. He also said she was “priestly” (sacerdotale) in her zeal for the Catholic Church’s apostolic labors in the Americas and other parts of the world.

Such language sounds strange to our modern ears. We assume that Catholic churchmen in eras long before Vatican II did not talk about laypersons, and certainly not laywomen, in such terms. But this is due to our general lack of awareness of traditional forms of lay patronage and leadership in the Church that were largely overthrown, abolished, or reformed into very different things decades before most of us were born.

That larger story is for another day. Here, I want to say more about this “priestly” duchess, whose dramatic life I will present more fully in a forthcoming book. Specifically, I will highlight D’Aiguillon’s contributions to the colonial-era foundations of the American church while clarifying her role in spreading French Catholicism elsewhere in the world.

For these and other achievements, D’Aiguillon was known and admired by kings, statesmen, archbishops, and popes in her time. Yet she is all but forgotten in ours. This is partly due to a longstanding historiographical tendency, where the Church’s missionary past is concerned, to relegate lay patrons to an inert backdrop—to regard their deep pockets merely as banks, so to speak—while focusing almost exclusively on the priests and religious engaged directly in evangelization. Not unrelatedly, the history of Catholic missions traditionally has been studied on a mission-by-mission and institute-by-institute basis, resulting in superiors of particular missions or religious orders, or sometimes bishops of missionary dioceses, appearing to be the primary or only ecclesial leaders involved.

By shifting our focus to lay patrons who assisted the launch and development of overseas missions, we begin to notice unexpected things. D’Aiguillon, for one, emerges as a leader, not just a passive underwriter, of the French church’s early modern global expansion. And she emerges as one who pursued a diversified, entrepreneurial strategy, encouraging and informally directing both spiritual and socially oriented missionary activities of a range of actors: bishops and secular priests, Jesuits, hospital nuns, members of other congregations including St. Vincent de Paul’s Congregation of the Mission (also known as Vincentians or Lazarists), and sometimes other laypersons.

The duchess’ story, in short, encourages us to reconsider what we know of—and how we talk about—the laity’s role in early American Catholic history and in the Church’s missionary history broadly.

Who was the Duchesse d’Aiguillon?

D’Aiguillon was able to become a lay leader in the Church of her time, and to extend her influence to many lands, partly because of the family she was born into. She was the beloved niece, protégée, and heiress of Armand-Jean du Plessis, the Cardinal-Duc de Richelieu, who was as King Louis XIII’s prime minister one of the most powerful and wealthy men of his age.

Marie-Madeleine de Vignerot du Pontcourlay was born in 1604. Her mother, Françoise du Plessis, was the eldest sister of the future cardinal and statesman. Her father, René de Vignerot, was a nobleman who had distinguished himself in battle and been rewarded by King Henry IV with a position at court. When Marie was a girl, Richelieu was an ambitious young bishop who was rising to political power with the help of Queen Marie de Médici, Henry’s widow and mother of the boy-king Louis XIII. In 1620, he used his niece as a bargaining chip in negotiations with nobles who were resisting the queen mother’s rule. Richelieu had his niece marry a marquis she barely knew, Antoine de Combalet, to seal a peace deal. She was 16 years old. In return, Richelieu was promised a cardinal’s hat by the groom’s own uncle, the Duc de Luynes, who had sway in the matter.

The marriage was short-lived. Combalet died in combat against French Protestants when Marie was only 18. Afterwards, Marie went on retreat with Carmelite nuns in Paris who followed the primitive rule favored by the newly canonized reformer and mystic Teresa of Avila. Among them, she soon desired to take vows and stay permanently in the cloister. However, Marie’s father having died, Richelieu asserted patriarchal authority over his niece and forbade her from becoming a nun. He took her into his home and had her serve as the second-ranking lady-in-waiting to the queen mother, who had a major hand in her son’s reign until she went into exile in 1630.

In this prestigious courtly position, Marie deftly assisted Richelieu’s further rise to power. The cardinal hoped she would do so most effectively by marrying again—with a great nobleman, perhaps even the king’s brother, Gaston d’Orléans. However, Marie resisted matchmaking efforts and remained a widow the rest of her life. This was a mixed blessing. It allowed her exceptional independence for a woman, especially as her wealth increased to monumental proportions together with Richelieu’s. But the unconventionality of it made her vulnerable to malicious speculation about the precise nature of her closest relationships, including with Richelieu.

With her exceptional intelligence and discretion, along with the work she put into becoming one of the great hostesses of the age, Marie became indispensable to her uncle in ways he had not envisioned. Indeed, by the time Richelieu reached the pinnacle of his control of the French state, Marie was one of the only people he truly trusted and cared for. She counseled him, spied for him, and sometimes stayed his hand against political enemies he might have jailed or executed. When he was busy with matters of state, she often acted on his behalf, meeting with clergymen, political officials, writers, artists, and others who could be useful to him. She helped choose beneficiaries of his patronage—including candidates for the French episcopate. She was known throughout Europe as a central actor in the political chess games going on in France during the fraught time of the Thirty Years War. And she learned from Richelieu and other prominent figures how to employ her position and wealth on behalf of talented individuals, institutions, and projects she favored for her own reasons.

In 1638, Richelieu had the king make Marie the Duchesse d’Aiguillon and a Peer of France, both in her own right and with the freedom to choose her own successor, male or female. This was unheard of in the Ancien Régime. It gave her powers very few noblemen then wielded, let alone women apart from the queen and several princesses of royal blood. Furthermore, Richelieu at his death in 1642 entrusted her with the major portion of his vast estates and fortune, which was one of the largest in Europe. He asked her to act in the place of a young nephew, the new Duc de Richelieu, in a range of capacities, including as the governor of the Norman port of Le Havre, which had strategic wartime value and was connected commercially to the New World. This all angered several relatives, including Marie’s spendthrift brother, François de Vignerot, whom Richelieu veritably wrote out of the will, and an ambitious uncle-in-law, Urbain de Maillé-Brézé, who (possibly because she had spurned his own advances) spread some of the ugliest rumors about Marie.

Marie was sued many times by relatives and others with grievances against her and the deceased cardinal. Some of the bad blood was due to her political alignment during the Fronde civil wars with the queen regent Anne of Austria, Louis XIII’s widow, and later with the “absolutist” administration of Anne’s son, Louis XIV. At the same time, some relatives were frustrated by how much wealth and attention Marie gave to Catholic apostolic and charitable endeavors—going far beyond what was socially expected of a courtly widow of the era.

The duchess’ interests in this regard initially were focused on North America.

Early contributions to the French American church

D’Aiguillon’s initial involvements in French colonial America developed in tandem with Richelieu’s. After his death, she became more creative and ambitious with respect to establishing French Catholic ministries abroad. This eventually earned her formal recognition from Pope Alexander VII for all she was doing for the Church’s apostolic expansion.

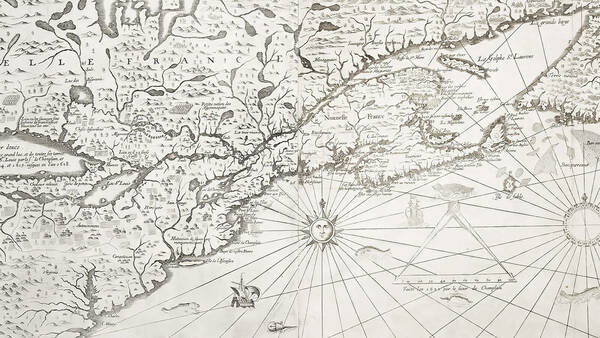

Marie’s early interest in America stemmed from her privileged knowledge of French activities there since the days she was a lady-in-waiting. Antoinette de Pons, who was the Marquise de Guercheville and the queen mother’s highest-ranking lady, was an investor in early French mercantile and missionary activity in Acadie, a colony that included parts of present-day Maine and Canada’s Maritime provinces. And in 1627, Richelieu established a merchant company for Québec and other French settlements and trading posts in the Saint Lawrence River Valley. Investors in this Compagnie de la Nouvelle-France were interested in the fur trade, agriculture, and lumber and minerals, but they also sponsored Catholic missions among the Hurons, Algonquins, and other native peoples of the region, favoring the Jesuits, especially, to staff them.

Marie was communicating with the Jesuit superior in Québec, Paul Le Jeune, by 1634. Le Jeune shared some of their letters with readers of his Relations de la Nouvelle-France, which were best-selling books published annually in Paris on French engagements with Native Americans. Utilizing the Relations to raise interest in what she herself was up to, Marie by early 1636 had wheels in motion for an innovative charitable hospital project for Québec. By the following year, Marie was the foundress of the Hôtel-Dieu du Précieux-Sang, a charitable hospital staffed by members of a new women’s religious congregation she favored, the Canonesses of Saint Augustine of the Mercy of Jesus.

Marie insisted that the hospital cater to sick and infirm Native Americans more than to the local French colonial population. It was the first hospital in the continent north of Spanish Mexico. The Augustinian canonesses who staffed it, known sometimes as Hospitalières, were some of the first women ever sent from Europe as missionaries. They were, furthermore, capable nurses, informed about the latest medical practices and committed to orderly and sanitary conditions for their patients—something not yet standard in European hospitals. They were also deeply prayerful and serious about the transcendent purposes of their work among the poor: communicating Christ’s love to patients, they were interested in the health of souls as well as bodies.

All of these things appealed to their founding patroness. As the project moved from vision to reality, Marie laid out considerable sums of cash and raised more cash from others for various aspects of the project she specified and monitored. She also chose the nuns who would be sent to America, negotiating with the Archbishop of Rouen, François de Harlay de Champvallon, who authorized their release from their original community in Dieppe. When a ship that had some of her cash as well as several nuns and medical supplies on board was threatened by Spanish vessels when departing France, she had Richelieu order the entire French naval fleet parked at Le Havre to escort it into safe Atlantic waters. And she directed, as much as was possible from Paris, activities of the Hospitalières and the Jesuits who served as the hospital’s chaplains. One thing she insisted upon, for example—at a time when Jansenists in France were promoting a pessimistic soteriology—was that the priests and nuns should emphasize Christ’s desire to save all human beings. This was a message she communicated in her correspondence, in the plaque she required to be hung over the hospital door, and in the artwork she commissioned and shipped to the Hospitalières—especially a large-format Crucifixion (later lost in a fire) depicting her, her uncle, the Blessed Mother, Saint John, and a group of Native Americans all together in humble postures at Christ’s feet.

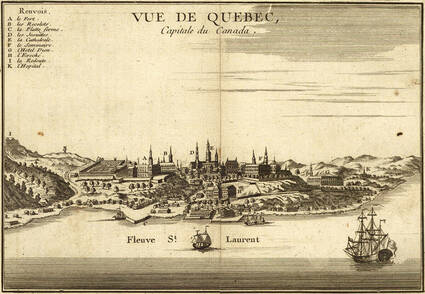

The Hôtel-Dieu de Québec was run by the Augustinian women until the time of Vatican II. It remains in operation today as a teaching hospital affiliated with the Université Laval. Local memory of D’Aiguillon’s role as its foundress persists, so where the duchess’ legacy in the Americas is remembered at all, it is typically in connection to the hospital, which she supported, assisting its expansion, for the rest of her life. But her involvements were more extensive than that.

I will clarify these involvements in detail in my book on D’Aiguillon, which is forthcoming from Pegasus Books. They include support of the Jesuits’ missionary labors, partly by facilitating their relationships with Richelieu and other metropolitan patrons of evangelistic and charitable projects in North America. Marie was also a major patroness of Father Jean-Jacques Olier in Paris at the time of the establishment of a seminary at the parish of Saint-Sulpice and an organization for missionary and charitable works in New France, the Société de Notre-Dame de Montréal, with which other prominent laypersons were involved. Sulpician missionaries would begin work in Canada in 1657. Marie appears also to have been involved with a later decision by Louis XIV to resurrect a Franciscan Récollet mission in New France that Richelieu had not favored.

Also, in this same period, Marie took part in the organization of early French missionary activity in the Caribbean. In 1635, she and Richelieu together chose a Dominican priest in Paris, Raymond Breton, who later authored a Carib catechism and Carib grammar, to lead a mission among natives of Dominica, Martinique, Saint-Christophe (St. Kitts), and the islands of Guadeloupe. Later, as the acting governor of Le Havre and a major shareholder in a new merchant company, the Compagnie de la France Équinoxiale, Marie had a say in the choice of clergymen and the kind of missionary labors they would engage in a colonial effort in French Guiana. Her patronage was acknowledged publicly in the Relation du Voyage des François fait au Cap du Nord en Amérique, which appeared in Paris in 1654 and was authored by the merchant company captain Jean de Laon, the Sieur d’Aigremont.

Establishing the Diocese of Québec and the MEP seminary

Marie’s most significant contribution to the foundations of the Church in America unfolded behind closed doors and at the highest levels of ecclesiastical politics. Although she was not formally a member, the duchess was a driving figure in the activities of a secret society, the Compagnie du Saint-Sacrement—a fraternity of elite laymen and clergymen in France dedicated to the reform and renewal of the Church, sometimes in cooperation with particular French bishops and Crown officials, and sometimes in opposition to others. Marie with several members of this society, who held some of their planning sessions in the duchess’ homes, were behind the establishment of the Société des Missions Étrangères de Paris, its affiliated seminary (known for short as the MEP seminary) that would eventually send missionaries to many parts of the world, and a sister seminary in Québec that would train diocesan clergymen for assignments throughout French America. In another display of her influence, Marie furthermore played a decisive role in lengthy negotiations that led to Pope Alexander VII’s decision to allow the French to establish four missionary dioceses—including one in Canada—and thereby break up the longstanding monopoly on ecclesiastical, territorial map-drawing beyond the borders of old Christendom that the crowns of Spain and Portugal had enjoyed since 1493, the year of the famous papal bull on the matter, Inter Caetera.

Leading the effort in the 1650s to have Rome authorize these French missionary bishoprics was one of Marie’s most remarkable accomplishments as a non-royal layperson. Alexander VII praised her for it in a brief he issued in her honor in 1658. By the early 1660s, three such bishoprics were set up for Asia and a fourth for North America. They were under de facto French political control and bankrolled by Marie and, to a lesser extent, her friends in Paris. According to a plan proposed to Marie and her friends by a Jesuit missionary to Vietnam, Alexandre de Rhodes, several Frenchmen would, if Rome permitted, be consecrated as bishops of long-vacant, ancient episcopal sees in what had centuries before become part of the Muslim world—bishops in partibus infidelium—while in actuality serving as bishops, each with the title vicar apostolic, for mission lands newly accessed by European Christians.

Even many historically informed American Catholics today may be unaware that the first Catholic episcopal see established north of Mexico was that of Québec. It had jurisdiction, even up to the time of Bishop John Carroll of Baltimore, over vast regions that would become part of the midwestern and southern United States. It was erected first in 1658 by Alexander VII as the Apostolic Vicariate of New France. In 1674, as Marie lived to see, it was elevated as the Diocese of Québec—the diocese that contained French Louisiana until New Orleans became its own see in 1793.

Not coincidentally, the first bishop in Québec was an associate of D’Aiguillon and her friends. François-Xavier de Montmorency-Laval (whom Pope Francis canonized in 2014) was 36 when chosen for New France. He was one of the first French churchman to be appointed as a bishop in partibus infidelium. This occurred in the summer of 1658, when he was at the same time made vicar apostolic of Québec. Like several of his compatriots who would soon venture off to the Far East, Montmorency-Laval was formally appointed in Rome but consecrated as a bishop by the papal nuncio in Paris, in the presence of the Duchesse d’Aiguillon, her friends, and French officialdom. The Mass of Consecration took place at the abbey church of Saint-Germain-des-Prés on December 8, 1658. Montmorency-Laval also at this time took an oath of loyalty to the French monarch—something Marie approved of highly—before sailing to Canada, which he reached in mid-June 1659.

Marie’s role in Montmorency-Laval’s appointment was more behind-the-scenes than the one she played in the case of her protégé François Pallu, the first Vicar Apostolic of Tonkin, Laos, and parts of southwestern China, and the other clergymen who were chosen for missionary bishoprics in Asia. But her role was well known enough at the time of her death that Father Brisacier underscored it in his funeral oration:

“She advanced by her negotiations in the courts of France and Rome the sending of an . . . vicar apostolic [to Canada] who today is a titular bishop . . . This worthy prelate had the joy to see the secular and regular clergy of his diocese . . . holily united. But all those who agreeably enjoy those two fruits perhaps do not know that Madame d’Aiguillon was in part the tree which bore them, by the role she played in this episcopal mission. It is quite right to render back into her hands . . . public witness to this.”

Of Marie’s persistence generally in pushing forward the project of the four French apostolic vicariates, Brisacier declared, “She rose like an eagle above all obstacles.”

Connected to the establishment of the French missionary bishoprics was that of the MEP seminary on the Rue de Bac, close to Marie’s Parisian residence. Still active today, this MEP seminary is most famously associated with 19th-century missions in Vietnam and Korea aligned with the imperialistic French Third Republic. First recognized by Louis XIV in 1663 and by the Holy See a year later, it was and remains a project of an association of Catholic laypersons and secular clergymen.

Marie’s financial gifts to the MEP seminary were relatively modest, but she assisted the seminary’s development far beyond this. She convinced women and men of her acquaintance to donate funds and material support, such as library books, sacred artwork, and various necessities for the classrooms, chapel, and dormitories. She also directed Pallu, before he was nominated as a bishop for one of the new French posts in Asia, in his advocacy in Rome for the seminary project along with the new missionary dioceses. By this point, a number of clergymen were committed to the seminary project, all of them vetted by Marie and high-ranking members of the Compagnie du Saint-Sacrement. These clergymen included Vincent de Meur, a priest of strong anti-Jansenist leanings; Michel Gazil de La Bernardière, an archdeacon of the Diocese of Évreux who was especially vigilant about Catholic doctrinal orthodoxy; and an expatriated Scottish priest named William Lesley, a former librarian of the Sacred Congregation de Propaganda Fide in Rome.

Alongside such clergymen, Marie led early planning meetings and fundraising efforts for the seminary. Brisacier, who eventually served as the seminary’s superior, even credited her with the founding vision of the seminary, which he claims she articulated to several churchmen and laymen sometime in the 1650s. Marie leveraged her position at court to obtain by 1663 Louis XIV’s approval of the seminary project and the Parlement de Paris’ registration of royal lettres patentes for the new institution.

These developments constituted the seminary’s official birth under French law. It would not be for another year that Cardinal Flavio Chigi, Alexander VII’s legate and nephew, would confirm the seminary’s existence in the eyes of the Holy See. He did so faster than expected, however, in August 1664. This was no accident. His approval came immediately following a state visit to France in which Marie hosted him at her magnificent Château de Rueil, while the cardinal-nephew was en route to visit the king at Versailles. The duchess impressed Chigi to no end as a hostess while she spoke effectively with him about the seminary project.

Clergymen involved in the MEP project credited Marie for her leadership. Lesley, for example, wrote, “I praise Madame d’Aiguillon’s zeal in extending the faith, but even more so her wise conduct in taking steps so conducive to [the seminary’s] success . . . She has very wisely weighed the matter of establishing solid and durable means of sustaining ministers who propagate the faith.”

By the mid-1660s, the seminary was training clergymen who would eventually labor overseas under the direction of the new French vicars apostolic. Some of them would join Bishop Montmorency-Laval in Québec, and over time MEP missionaries would become active throughout North America. Although scholarly work has been done on the MEP seminary and its affiliated missions, the MEP clergymen’s activities concerning North America remain understudied. Less familiar than the MEP seminary in Paris, for example, is its sister seminary established at the very same time under Laval’s direction in Québec. Until 1760, it was closely tied to the seminary in Paris. Priests formed in it served French and Native American congregations in Canada, the Great Lakes region, parts of the present-day U.S. states of Maine and Massachusetts, and eventually in the Louisiana territory. These missionaries’ ties to the Duchesse d’Aiguillon and other lay patrons in both France and North America are ripe for research.

Reconsidering the lay foundations of the American church

The Duchesse d’Aiguillon was not the only important lay founder of Catholic ministries in French North America. There were a number of such figures, including the already-mentioned Marquise de Guercheville, the nobleman Jérôme Le Royer de La Dauversière and others involved with the Société de Notre-Dame de Montréal, and the noblewoman Marie-Madeleine de Chauvigny de La Peltrie, who founded and also joined the Ursuline community of early colonial Québec. French colonial governors, as well as families that settled in colonial Canada, were also involved in the build-up of the Church in New France. And the Relations and other sources from the time present to us an array of other, less familiar laypersons—male and female, French, French colonial, and Native American—who collaborated with, and were not only led by, members of the clergy and religious orders in the establishment of mission communities, schools that instructed indigenous and French colonial children in the Catholic faith, and medical missions.

Lay patronage and other forms of lay leadership in the establishment and development of Catholic missions and institutional life were crucial, too, in Spanish and Portuguese America and still await the modern scholarly attention that they merit. The contributions of lay elites to the development of the Church in English colonial Maryland and in the young American republic are a bit more familiar. Families such as the Calverts and Carrolls have long enjoyed a canonical place in the historiography of early American Catholicism, and the story of lay trusteeism in the Church in the young United States is also a relatively well-known, if controversial, subject.

At the same time, the very focus on themes such as lay trusteeism and the eventual eradication of it by episcopal authorities closely tied to Rome has had the effect of blunting open-ended inquiry into lay patronage and leadership more broadly in the early American church. Because the bishops came out victorious in the trusteeism battle and the 19th-century Church in America came to be led by many charismatic and influential churchmen and consecrated women and men, we tend to look back on the earlier period of American Catholic history through lenses colored by that teleology. We may be overlooking, as a result, the stories of unfamiliar lay Catholic leaders of the early American church who are as interesting, if not necessarily as powerful and wide-ranging in their activities, as D’Aiguillon.

The range and scale of Marie’s overseas projects were exceptional, to be sure, especially for a non-royal laywoman of her era. Because of the perspective on French and world affairs she had as Richelieu’s niece and as a fabulously wealthy and powerful French noble close to several reigning monarchs, she at times took leads from the Crown, which was accustomed—like the crowns of Spain and Portugal—to sponsoring a diversity of religious and charitable projects at home and overseas. Yet it is also clear that, over time, she influenced French royal sponsorship of overseas missions in the middle decades of the 17th century. Various missions she helped to conceive, establish, fund, and informally direct all benefited from royal funds she secured as well as donations from other private persons.

Exceptional though she was, D’Aiguillon reminds us that in centuries distant from our own, bishops and other clergy, along with consecrated men and women, were far from being the only primary, creative, and authoritative actors in the Church’s missionary expansion into the Americas and other lands. Her story shows that a shift toward the perspective of lay patrons and other lay leaders in researching and telling that history can reveal aspects of it that focused attention on a single religious order or missionary setting cannot. For example, one of the most striking features of D’Aiguillon’s foundational patronage of the Church in America was its diversification. She patronized a mixture of regular clergy and secular clergy, male and female religious, and institutions devoted to evangelistic and social-charitable works.

This was consistent with her approach in France itself, where she was a founding patroness of a wide variety of institutions, including many of the early ministries of Saint Vincent de Paul and the Congregation of the Mission, and in other overseas contexts, including Tunis and Algiers in North Africa, Aleppo in Syria, the island of Madagascar, and parts of East and South Asia. Over time, in these regions, she supported from Paris—and sometimes informally directed—a variety of French missionary, mercantile, and charitable actors, including Vincentians, secular clergymen affiliated with the MEP seminary, Jesuits, Discalced Carmelites, and laypersons who served the interests of both France and the Catholic Church as Marie (ever Richelieu’s niece in this regard) and other French patrons wished them to do.

Such diversification was part of a broader, entrepreneurial-ecclesial strategy Marie developed—a strategy that only a powerful, wealthy layperson, and not a bishop or religious superior, could conceive and pursue as freely as she did. She believed, not unlike investors who back a number of different ventures in order to spread out risk, that greater, longer-term spiritual and civilizational benefits would accrue if she nurtured different kinds of French Catholic institutions—innovative, experimental ones alongside tried and tested ones—some of which, she understood well especially after years of experience, would encounter unforeseen setbacks or even fail altogether. Where her overseas interests and investments were concerned, the risk of failure was omnipresent given the lack of ready and reliable information about conditions on the ground and ongoing conflicts with a range of actors—some of them playing out at sea, of course, between the French and their European rivals (Catholic and Protestant) for imperial expansion.

In sum, the lay patroness D’Aiguillon helps us to look freshly upon a period in Church history about which we have assumed we knew most of what is important to know. We find in the story of Catholicism in New France, and can find in other early missionary contexts of the Church’s history, a richer tapestry to examine than we thought was there—one featuring an array of ecclesial, apostolic actors and leaders who were not all churchmen and religious.

Thus it is that we 21st-century scholars and students of the past, more than the 17th-century churchmen who heard him in person, are surprised that Father Brisacier eulogized a laywoman in 1675 as “priestly” and like a bishop. We tend to look backward on the Church of past times with a modern conceit: that, at least in the Catholic world, lay leadership and appreciation of it were the discovery of 20th-century reformers such as the Vatican II authors of Apostolicam Actuositatem. Yet Brisacier thought nothing of referring to a French duchess as “another Saint Paul.” There are surely, then, other important lay leaders, female and male, of the Church of distant centuries still for us to discover and from whom we can learn.

Bronwen McShea is a visiting assistant professor of history at the Augustine Institute Graduate School, a writing fellow at the Institute on Religion and Public Life, and the author of Apostles of Empire: The Jesuits and New France (Nebraska 2019). Her biography of the Duchesse d’Aiguillon, Peer of Princes, is forthcoming from Pegasus Books and draws from research she did as a 2018 recipient of the Cushwa Center’s Mother Theodore M. Guerin Research Travel Grant.

Feature image: Early map of New France, circa 1632. Courtesy of Toronto Public Library Special Collections.

This article appears in the fall 2021 issue of the American Catholic Studies Newsletter.

Originally published by at cushwa.nd.edu on October 11, 2021.