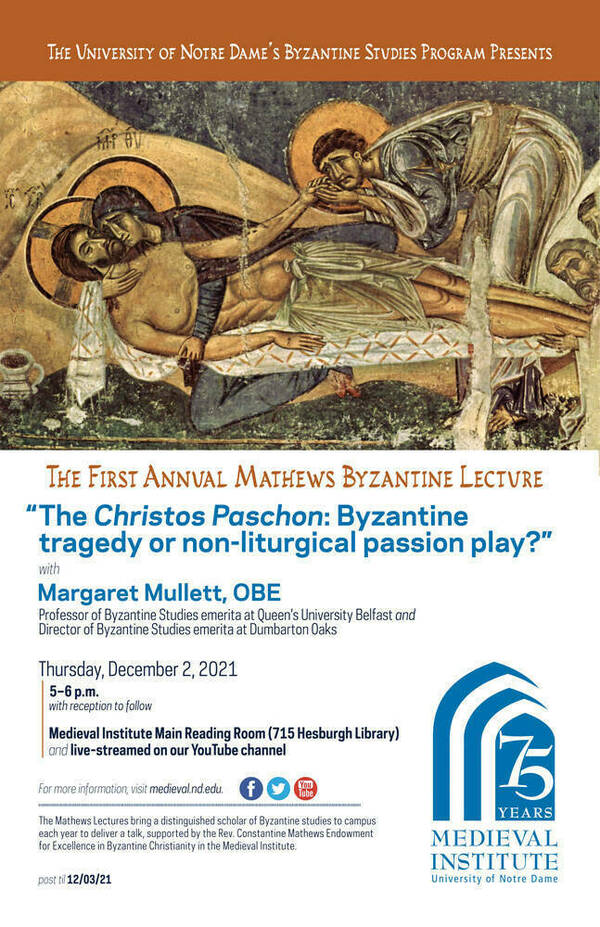

On Thursday, December 2, 2021, Margaret Mullett delighted her live and online audience with a talk entitled "The Christos Paschon: Byzantine tragedy or non-liturgical passion play?", the inaugural lecture of our Mathews Byzantine Lectures. This lecture series brings a distinguished scholar of Byzantine studies to campus each year to deliver a talk, supported by the Rev. Constantine Mathews Endowment for Excellence in Byzantine Christianity in the Medieval Institute.

Mullett, who was honored by the Queen of England with an appointment to the Order of the British Empire for her scholarly contributions, including her work as a Professor of Byzantine Studies at Queen’s University Belfast and as Director of Byzantine Studies at Dumbarton Oaks, discussed Christos Paschon. This text is attributed in all manuscripts to Gregory of Nazianzos but is generally now believed to be a product of twelfth-century Constantinople.

The 2602-line drama, which covers the period from Maundy Thursday to the mission of the Apostles, confounds both Byzantinists and Classicists with its blurred boundaries between religious and secular: while telling a religious story, it claims to be a Euripidean tragedy and includes frequent quotations from ancient Greek tragedy.

Mullett focused on five major qualities of the text: plot, content, texture, performance, and genre. The plot includes three major sections—Christ's crucifixion, burial, and resurrection—focusing especially on the experiences of the Virgin Mary (Theotokos) and John the Theologian. Its content expands greatly on the information offered in the Gospels by placing Mary at Christ's deposition; is also organized in a different fashion, with 11 laments, 5 messenger speeches typical of Greek tragedy, and 5 theological speeches.

Despite the theological concerns of its plot and content, its texture is secular. Almost a third of the text consists of half-lines, lines, and chunks from Euripides, particularly from four of his plays: Medea and Hippolytus, which dominate the first half the text, and Rhesus and Bacchae, which are more frequent in the second.

Mullett compared this use of quotes to architectural spolia or brushwork in painting: the words of tragic heroines in the mouth of Mary Theotokos create a sense of polyphony, introducing implicit comparisons and contrasts concerning their tragic motherhood. While the text also references the Bible, these references are thinner (generally a couple of words per page) and frequently consist of individual words or paraphrases, rather than phrases or sentences.

It is highly debated whether the text were performed, but Mullett argues that it was likely read aloud in a non-liturgical context as a shared social experience. This makes the genre difficult to determine. Mullet argued that it was likely an innovative trilogy of three individual tragedies due to its three actors and chorus, messenger speeches, and use of deus ex machina, although she acknowledged its happy ending, length, and meter make this matter difficult to settle for certain.

This fascinating text and talk left the audience excited to read the text in its entirety and grateful for the Matthew Byzantine Lectures, which will certainly be an annual highlight at the Medieval Institute!

Originally published by at medieval.nd.edu on December 06, 2021.